It Seems I Have Found Myself In Another Mysterious House

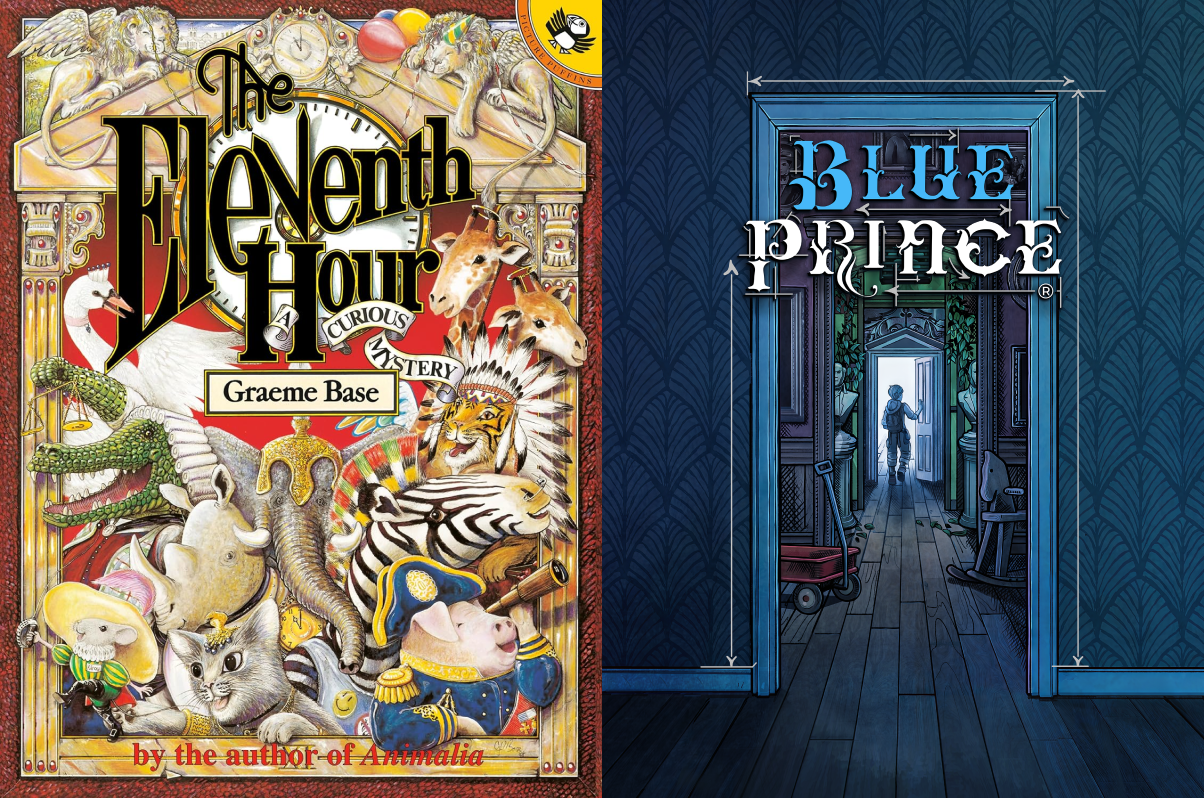

One Hanukkah many years ago, my uncle gifted me a picture book: The Eleventh Hour, by Graeme Base. Its vividly painted cover featured a gathering of animals in costumes, some of which have aged better than others. There’s also a prominent clock, and a subtitle wending its way through the main lettering: “A Curious Mystery.” As you open this book, you are taken into a story of an elephant throwing a birthday party at his mansion, preparing tons of food to feed all his animal friends. (This elephant, Horace, lives in luxury and, to his credit, wishes to share his bounty.) The guests show up, things get a little out of hand, and the vast feast disappears, consumed before the scheduled hour by some scoundrel.

That isn’t a spoiler. The spoiler is everything else about the book, which in fact ends by inviting you on a quest to start the book over and figure out who did this. Every little detail of the art in the house, and the times on the clocks, and the codes etched into walls and around the borders of scenes, contribute to a process where you can actually puzzle out who swiped the birthday luncheon while everyone was busy celebrating Horace.

I loved this book, once I got over a ten-year-old’s mortification at receiving a picture book about animals when I’d clearly moved on to devouring Redwalls. It rewarded my attention wherever I applied it, and in hindsight felt like the honing of a tool first forged to find Waldo — graduating from mere noticing into analysis. The puzzles, codes, and metatextual elements of The Eleventh Hour created a new space above, around, and between the pages of the book itself, a space where I could play. Also, and I admit I resorted to this the second I had a plausible theory: There was a really easy substitution cipher in the back of the book that just told you who did it, along with a sealed dossier explaining all the clues. Look, I had Redwalls to read.

I remembered “The Eleventh Hour” recently, when I played a new video game about, of all things, an uncle presenting his nephew with a curious mystery set in a mansion. In Blue Prince, which absolutely just took over my week, you stand to inherit this uncle’s famed estate, provided you can discover its notorious secret room. Blue Prince is a game “like Myst” — set in a fanciful location, laden with architectural and environmental puzzles, slowly telling a story that it encodes in the solutions. Crucially, Blue Prince ALSO takes a cue from modern drafting roguelites like Slay the Spire and Slice & Dice, games built around repeated runs that unfold differently depending on your moment-to-moment decisions in a randomized environment, a combination scholars have termed “The Rob Zone.”

This is in fact the big hook the whole game pivots around: The layout of the house changes every day. When you open a door, you don’t know what’s behind it; instead, you draft the next room from a pool. Step by step you build that day’s version of the mansion, slowly accreting clues about the secret room that stands betwen you and your frankly questionable inheritance. How do you even value a house with up to 45 rooms, a variable number of which are bedrooms and (so far) at most one of which has a toilet?

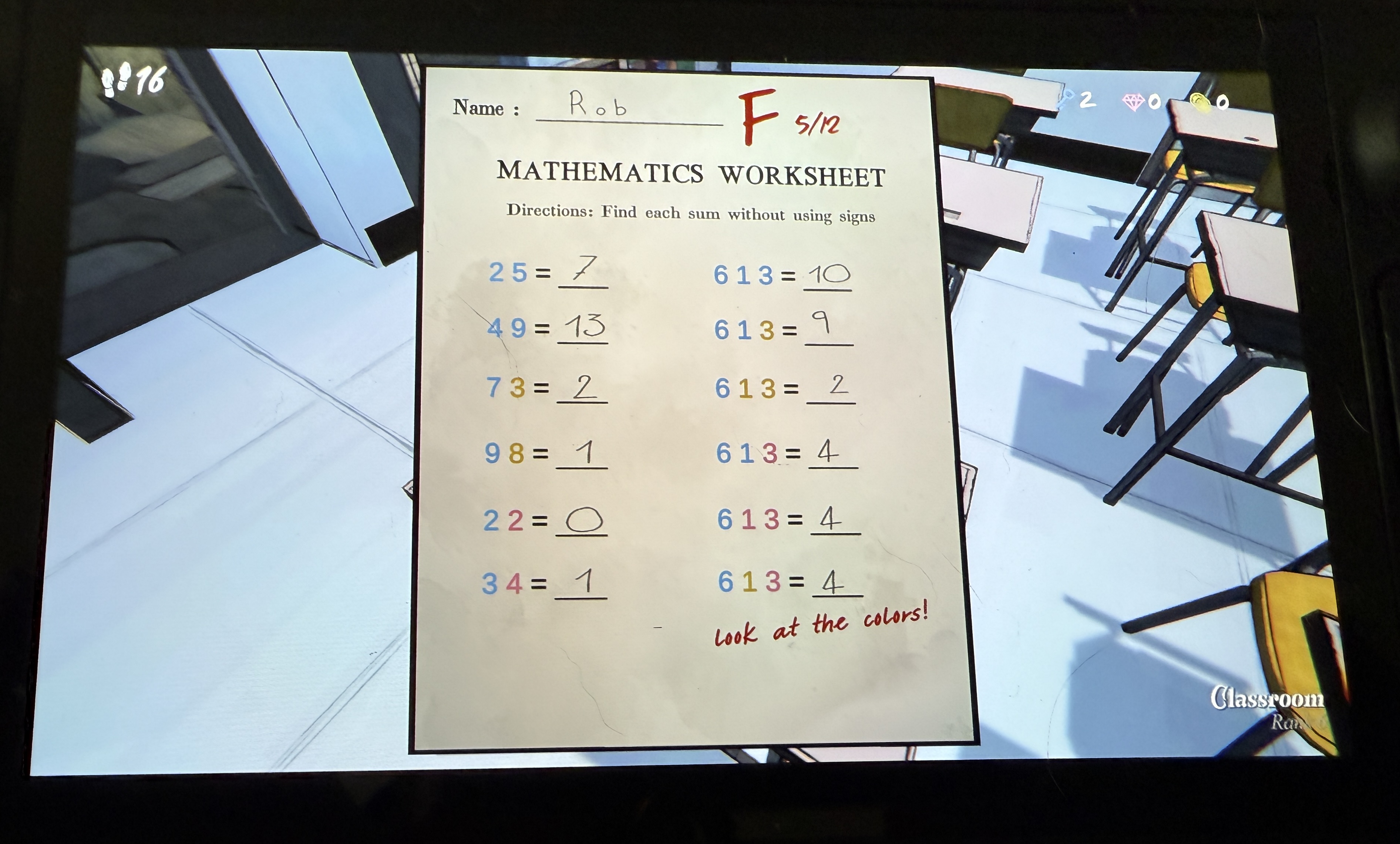

I haven’t beaten Blue Prince yet, I’m still busy being enthralled by it. Maybe I’ll have more to say when I’ve rolled credits, which also seems like it’s just the beginning of a whole different journey with the game, as is the fashion these days. I’ve already seen enough to give Blue Prince my strong endorsement, even though it totally sold me out on my math skills:

Probably not a spoiler? I don’t know, it’s hard to tell.

Probably not a spoiler? I don’t know, it’s hard to tell.

If you’re remotely interested in environmental puzzles, deep embedded stories, or experiences that live in an interesting way in your mind, Blue Prince is your shit. The way this game scrambles the concept of memory — especially around something like an old house — it really gets close to what memories of old houses actually feel like, for me. Sure there are some remembered places I can recreate room by room if I really focus, but more often those images jumble together and I experience them sort of out of order, rearranged. It felt like Blue Prince reverse-engineered that phenomenon to build a clear sense of this fictional house in my mind, even when I’ve never experienced it the same way twice.

I’m not exactly boosting an underdog here. Blue Prince is popular, and I think one thing it’s doing successfully is activating players’ memories of how they were introduced to this kind of mental challenge, at some point, by some kind of thoughtful other person. One of the most notable aspects of Blue Prince for me, so far, is how it stands out among its run-based randomized peers for its nonviolence; roguelites as a genre, and I say this as a fan, typically hyper-focus on combat. Blue Prince, instead, seems more concerned with abstract concepts like the motivations of the questgiver and the care of the game designer. It’s just trying to throw a good party, and I think it’ll be a new generation’s Eleventh Hour.